'Different starting assumptions'

How women in evolutionary biology changed science. And, one week until the launch of Mother Brain: How Neuroscience Is Rewriting the Story of Parenthood

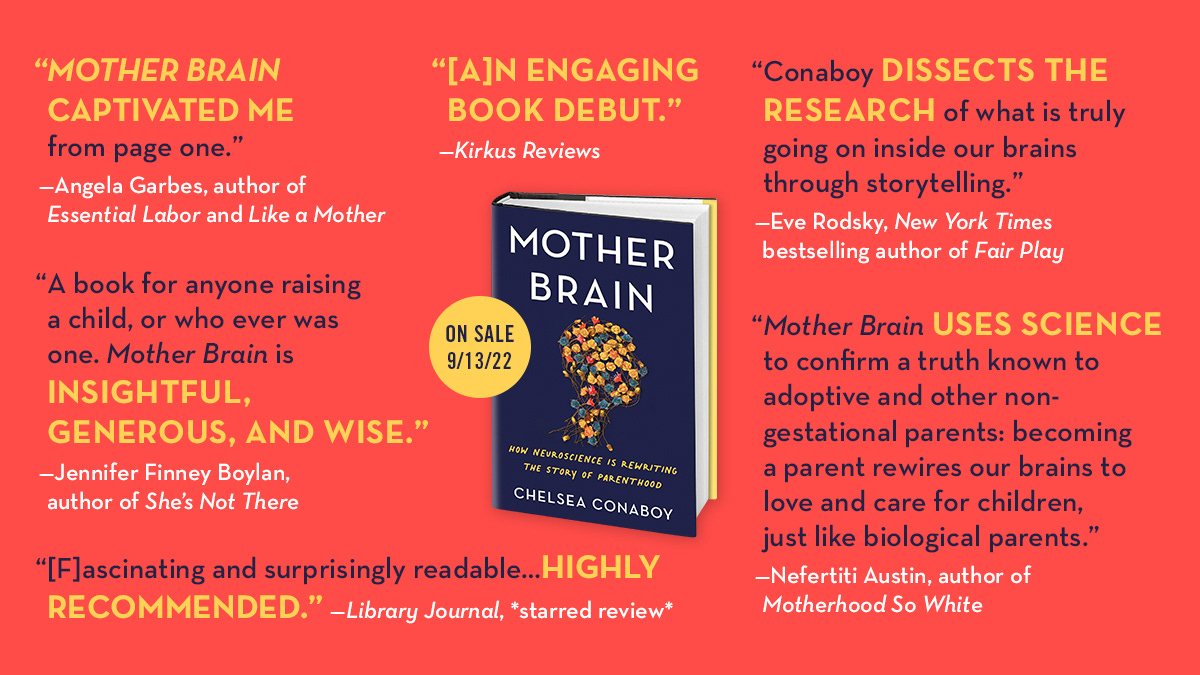

The launch of Mother Brain is one week away, and its entry into the world so far has been exciting, to say the least. The Sunday Times of London called it “a book that will inspire today’s new parents: socially alert, inclusive, kind.” Science Magazine recommended it as part of their fall reading list, for “a season of reflection.” In a starred review, Publishers Weekly said Mother Brain “should be required reading for all caregivers.”

Then there was the New York Times. An adapted excerpt about the myth of maternal instinct—as an innate, automatic, distinctly female capacity for caregiving—ran on the cover of the Sunday Opinion section last week, with amazing illustrations by Csilla Klenyánszki. It is a dream to have this kind of coverage for my first book, and more than a little surreal to have a chapter I wrote during the deep quiet of the early pandemic now so widely read. I’m grateful to the editors at the Times for seeing the value in it and giving it so much space.

Thousands of people weighed in through the comments section and on social media. I’ve received dozens of thoughtful personal notes from researchers and parents. And I’ve done my best to keep in perspective the angry and dismissive comments, often from people who didn’t read much beyond the headline. I’ve worked in newspapers long enough to understand that’s just how it goes, but I’m not going to pretend it doesn’t cost me, in energy and time and sleep. Particularly frustrating are the comments from scientists—men, overwhelmingly—who argue that the only way to see the notion of maternal instinct as a myth is to disregard biology entirely.

The thing is, Mother Brain is dedicated entirely to exploring the biology of the transition to parenthood. The neurobiological changes that accompany new parenthood are profound, dramatic and long-lasting. But they are not what we’ve been told they are. My goal in writing this book was to put the biology first, in fact. To remove the shroud of entrenched beliefs about what maternal instinct is in order to look squarely at what this developmental life stage really requires of us.

I’m far from the first person to do this. Sarah Blaffer Hrdy is a renowned anthropologist and primatologist whose work critics of the Times essay have cited, as if her research discounts my argument. I’m not sure those critics have read Hrdy’s work closely enough. Otherwise, they might have known that Hrdy’s whole career has been dedicated to challenging long-held beliefs about mothers, across species, and using science to write a truer story.

I cite Hrdy’s work extensively in Mother Brain and interviewed her multiple times while reporting this book. The very first question I asked her was whether the phrase “maternal instinct” holds any real value today. She has complicated feelings about those two words, too, and told me, “There is nothing like an innate switch that gets turned on so a woman is driven to have or unconditionally love her baby.”

There’s more to say about this point, and I’ll return to it, but for now I thought I’d share a short excerpt from Mother Brain about how Hrdy and her colleagues began challenging what they’d been told about mothers, from the very start of their careers. Scroll down for more about what’s happening next week:

When Hrdy, the anthropologist and primatologist, started graduate school at Harvard University in 1970, biologists still held tight to the notion that the whole purpose of mothers “was to pump out and nurture babies.” The belief was especially strong in the field of primatology, according to Hrdy, “where the creatures being studied were so similar to ourselves” and the people more prone to impose beliefs upon them. Hrdy would soon become part of a first generation of women in her field, many of them also mothers to young children, who found themselves repeatedly running into questions that couldn’t be answered by the evolutionary theory they’d been taught.

Jeanne Altmann, along with her husband, Stuart, studied baboons in Kenya and recognized them as “dual-career mothers.” Baboon mothers spend three-quarters of their day doing what Altmann described as “making a living,” walking with their group to feeding areas and digging for bulbs and grass corms to eat, all while avoiding predators and tending to their infants’ needs. Altmann wanted to know, how did they manage their time? How was their social status changed by motherhood? How did reproductive history affect their lives over the long term? Meanwhile, anthropologist Barbara Smuts wondered about the purpose of the long-running friendships that develop between male and female baboons, and sometimes between adult males and infants who are not their offspring. (Altmann called these males “godfathers.”) Smuts asked, “What were these large, ruthless fighters doing in the ‘female domain,’ looking slightly out of place as they cuddled and carried tiny infants?”

Hrdy herself began asking provocative questions about langurs, a type of leaf-eating monkey, and the males among them who would sometimes kill infants with apparent “collusion” from the mothers, who would later mate with those same males. What role could such incidents of infanticide possibly play in advancing the survival of a species? And, looking across the animal world, what about those species in which mothers are the ones doing the killing or, more commonly, abandoning offspring under pressure from food shortages or predation or so they can be free to mate again?

A female, in Darwin’s thinking, is generally sexually passive, choosing among the mates who compete for her attention and beyond that having little influence on the fate of the species. But nearly a century after Blackwell’s call to action, the work of these women and many others made the idea that maternal biology renders a female “coy,” wholly self-sacrificing, or inherently inferior seem downright silly.

Slowly, a new picture emerged of primate mothers who plot, in a sense, for evolutionary success and rely on others to help them achieve it. Mothers, Hrdy wrote, were “just as much strategic planners and decision-makers, opportunists and deal-makers, manipulators and allies as they were nurturers.” Female sexual and maternal behavior varied across and within species, shaped by competing demands. Maternal care—let alone maternal love—was not automatic. Within that framework, babies had to become agents of their own survival, compelling parents to care for them.

If [Jay] Rosenblatt’s work cracked open the door, allowing researchers to look with fresh eyes at the biological transformation that comes with new parenthood and the ways that babies and parents act on one another, the work of evolutionary biologists in Hrdy’s era pushed it open. “More women in evolutionary studies changed science,” Hrdy told me. “It wasn’t that we were doing science differently. It was that we were—we had different starting assumptions.”

But the work of these primatologists, especially Hrdy, also has drawn the ire of some feminist thinkers. Ten years after Hrdy published Mother Nature, her 1999 tome on the biology and behavior of mothers and babies, she followed it up with a book about the roles extended family members and other caregivers have played in child-rearing throughout evolutionary history. French writer and philosopher Élisabeth Badinter called the determinism she saw in Hrdy’s work “loathsome.” In 2010, Badinter published The Conflict: How Modern Motherhood Undermines the Status of Women, in which she objected to the rise of attachment parenting and its promotion of a “return to a traditional model” at the expense of a woman’s identity. She made many good points about the jumps in logic required to sustain maternal instinct as a tool for social control. She also faulted the evolutionary biologists who study primates and see in them clues about human mothers.

Although Badinter declined to be interviewed for this book, she told me by email that she thinks there may be room for neurobiology in the study of motherhood, but only as a factor secondary to societal influences. In her book, she wrote that the link between human and primate is weak. Environmental context, social pressure, and a mother’s individual psychological experience all carry more influence than “the feeble voice of ‘mother nature,’ ” she wrote. “As soon as we bring nature into the discussion,” she told the magazine Le Nouvel Observateur in 2010, “there is no way out.”

I see Badinter’s point. The natural history of motherhood has proven too often to be a cage. Maternal instinct, to twist Lorenz’s metaphor, has been the impenetrable lock on the door. But becoming a mother is a major biological event rooted in evolutionary history. New parents do experience a dramatic neurobiological change, and that change is particularly intense for gestational parents. Failing to acknowledge that is a trap in itself, if only because it leaves space for the specter of those old ideas to fill.

The transition to parenthood builds on the inherent flexibility of the brain, molded by both hormones and experience, influenced by the inherited coding of our species and by the peculiarities of our own brand-new babies. It is a process—one of short-term upheaval and long-lasting, continual change. Overwhelming and purposeful. In the early months, as the next chapter makes clear, it can be shaped as much by worry as by love. When you are in it, the voice of nature may sound like many things, but it is certainly not feeble.

(Excerpted from Mother Brain: How Neuroscience Is Rewriting the Story of Parenthood.)

Coming up:

SEPT. 15: I’ll be in conversation with Lynn Steger Strong to celebrate the launch of Mother Brain, at 7 p.m. at Mechanics Hall in Portland, Maine. RSVP here. While you’re here, preorder Lynn’s gorgeous new novel, Flight—you won’t regret it.

SEPT. 20: I’ll talk with Boston Globe reporter Stephanie Ebbert at Porter Square Books in Cambridge, Mass., at 7 p.m. RSVP here. (NOTE the date change: This event was originally scheduled for Sept. 19.) And, watch for a perspective piece coming from me in the Globe Magazine!