Imagining a robot mother in the era of AI

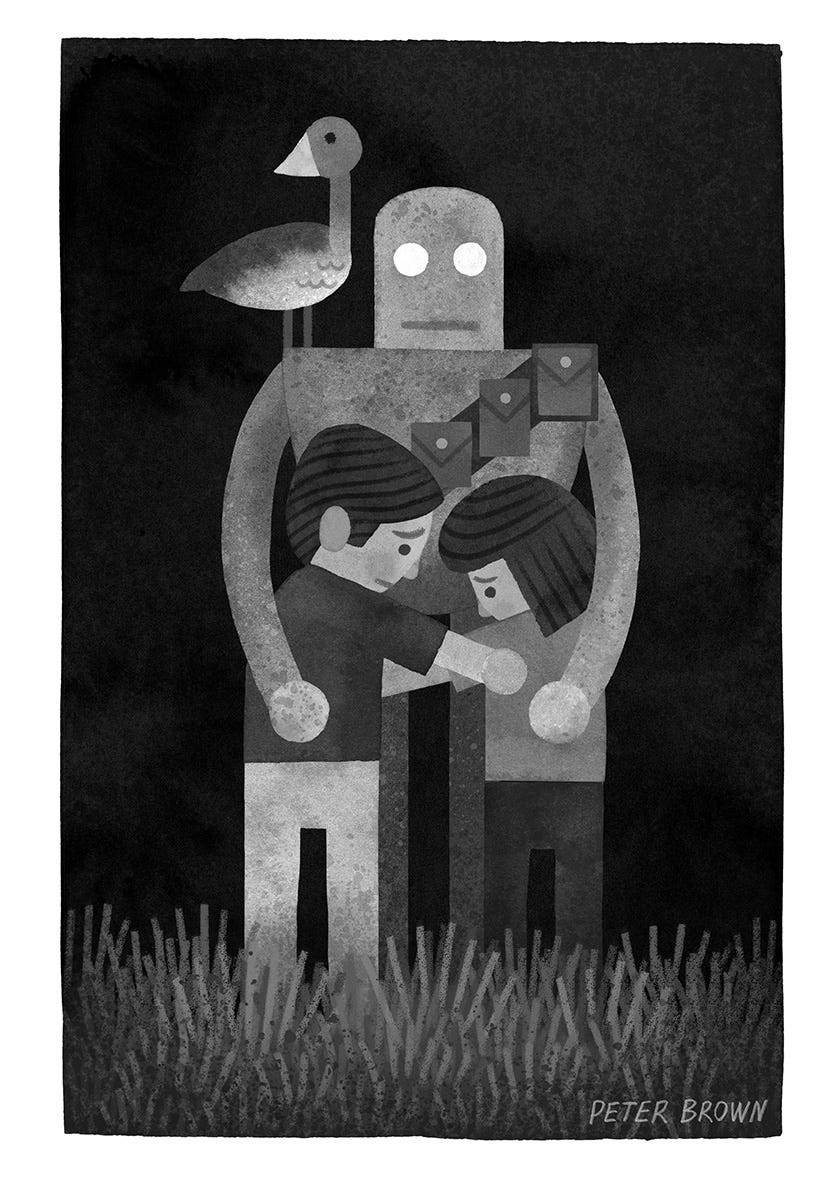

Peter Brown, author of The Wild Robot series, talks about creating family and what it means to tell a story about a robot who does good.

We were listening to The Wild Robot, again.

In a summer of roadtrips, this was our third round with the first two audiobooks in Peter Brown’s series about Roz, a robot who finds herself on an island uninhabited by humans and builds herself a life there. We had already reread the printed books, too, in anticipation of The Wild Robot Protects, book 3, which was coming in September.

The truth is, I didn’t mind.

My boys, ages 6 and 8, love the animal family that Roz builds on her rocky, remote island, and the giant “nest” she creates, like an oversized beaver dam, where she raises her son, an orphaned goose named Brightbill, and shelters her friends. They love the suspense when Roz goes on the run, trying to escape robots that seek to contain her, the one who has gone rogue.

I love Brown’s spare prose and the complexity of the relationships he has created. The conversations between Roz and the animals, between Roz and her maker, about connection and difference and what matters, have become part of our family culture.

And, there’s another reason I love Roz that feels all my own. I love the mother she is and the way she gets there.

In her first days caring for Brightbill—the goose is orphaned as an egg, when Roz accidentally crushes his family’s nest—Roz does not know what to do, despite a computer brain full of information.

She watches animals with their young, she listens to their advice, she tries and fails and tries again. She is curious and attentive to the gosling who needs her, and their relationship—their love—develops from there.

She offers, in my view, a true depiction of new motherhood, stripped of so many of the tropes and expectations we pile upon human mothers. She is a hunk of metal and wire, and she is trying her best. She is learning.

On the road, my husband turned to me and said, “You should really interview Peter Brown.”

I sent Brown an email, unsure he would understand why exactly a journalist who writes about the neuroscience of parenthood would want to interview him about his middle grade sci-fi series. He responded right away.

The conversation that followed was so rich that I asked Brown, who lives a couple hours from me in Maine, if we could do a live event together. Then and in conversations that followed, I learned that Brown is a deeply thoughtful person who cares about telling great stories and about what those stories will do in the world.

Earlier this month, we got together at Portland’s Mechanics’ Hall for a conversation about parenthood and AI and the weight of the stories we tell. The interview below is from our first conversation, condensed and edited for length and clarity.

I went back and read the New York Times review of The Wild Robot from 2016, and I was surprised to see that the mother-son relationship between Brightbill and Roz was not mentioned at all. To me, that’s the heart of the book.

Brown: People read this book and respond really strongly to it, and sometimes I'm not even sure they realize that, what I suspect is, they’re really responding to that relationship, even though it’s kind of low-key compared to the action and the high concept and all this other stuff. That’s what gets written up in the New York Times. But I think what really keeps people turning those pages is that they care about the characters, and the reason they care about the characters is because they’re relatable.

They’re relatable because everybody has a parent or a child or has some sort of connection with, or can relate to their relationship in one way or another.

You write about the process of Roz becoming a mother so directly. It seems as though the fact that Roz is a robot allows you to do that in a way that you wouldn’t get to if this was a human mother.

Brown: I totally agree. Yes. Roz is a single mom, and I was raised by a single mom. I don’t think it is any coincidence that my brain went there, without me even really intending it to. If I were to write a story about an actual human single mom, it would be almost—coming from me, there would be a danger that it’d be too on the nose. I don’t feel like it would’ve been as interesting.

Because Roz is a robot, it allowed me this freedom to really explore motherhood, childhood, family relationships in a way that wasn’t preachy, that wasn’t predictable. Even though a lot of the stuff that I think people respond to the most is kind of the everyday—watching Roz and Brightbill get into an argument and Brightbill flying away in a huff and her finding him and them having a thoughtful conversation—that’s pretty normal, everyday stuff for parents and kids. And yet you package it in a robot and a goose on a wild island, and suddenly it’s fascinating.

Don’t get me wrong, I think real family dynamics are totally fascinating also. But for little kids, for 8-year-olds or 10-year-olds or whatever, I think this is a way to present those ideas to them in a way that they can really have fun with, and it’s entertaining and it’s exciting and it’s delicate and it’s personal and all this other stuff.

There’s a part in the first book where an older goose is giving Roz advice on how to raise Brightbill and she tells the robot, “You’ll have to act like his mother if you want him to survive.” And the narrator says, “There was that word again—act. Very slowly, the robot was learning to act friendly. Maybe she could learn to act motherly as well.”

I write a lot about the idea of maternal instinct and where it came from and why we think it’s based in science and what actually happens when a person has a child. What happens is we learn—it’s a learning process. It doesn’t happen automatically. And here is this perfect acknowledgement of that—she has to learn to act motherly, and she does it by using all of this information in her head and through the advice and support of the creatures around her. And she becomes a mother.

It is such a poignant framing. You just let her be—to grow into it in a way that we all have to.

Brown: I was juggling a lot of things with this story. Obviously, at its heart, I wanted this story to be believable, even though it sounds crazy. If you were to open the book halfway through, it would seem outrageous. But the step-by-step progression where, if we follow this robot gradually learning about this island and about the animals and the wilderness, and then even about parenthood and herself and all this stuff—that was really important to me. Her learning about being a mom was part of the deal.

The reason I came up with their relationship in the first place was because I was worried that readers would have a hard time caring about a robot for 280 pages as a main character. So many of the books and movies that we watch with robot characters, the robots are usually secondary characters, with a few exceptions. So I was thinking, “Well, how am I going to keep readers interested?”

I wanted to win everybody over, as many people as I could. I thought, if Roz has a family, I think people will care about her more. And obviously she couldn’t have one biologically, but she could adopt some sort of orphaned creature, and we could watch that whole process unfold.

I think parents, adults reading this book with kids, would relate to it from one level, and kids would relate to it on another level. It was pretty exciting as that started unfolding in the development of the story, to watch my story turn into something else, turn into something better than what I had expected and more interesting and more personal.

Roz has to figure out how to raise this animal, and she might have a brain with a lot of information, but it’s not going to be enough. She’s got to observe animals. She’s got to talk to other geese. She’s got to have these conversations and get advice. Once I started going down that path, there was a certain logic to the whole progression that she goes through, and the finished result is characters that, I think, we care about a whole lot more. Roz in particular we care about a whole lot more because we watch her stumbling through this process of making a family.

At the very end of the chapter called “The Mother,” you write, “No Gosling ever had a more attentive mother.”

The science of what happens to the parental brain—it’s all about attention. Attention is what a newborn needs, more than any other thing. And a parent’s attention is essentially hijacked by a baby. That is the thing that makes you grow into a mother, into a parent. All of your attention is given to your child, and because of that, you keep them alive and you learn really quickly what they need and how to respond to it.

You got so much right in your portrayal of Roz as a mother and I’m wondering, where did that came from? Was it research or just your own understanding of human nature?

Brown: Oh, well, that’s a good question. I did a lot of research.

As I was thinking about Roz learning how to be a mom, I just thought that one of her natural abilities would be attentiveness, right? She’s going to look at things. She has this sort of computer brain that probably remembers more or less everything that she experiences. She won’t forget anything. She’ll remember every little detail. She notices everything. Literally, no human child would have had a more attentive mother than Roz either, because she’s just an attentive character.

It felt right on the more personal side. It felt like she’s growing into that role. We’re watching her become a better mom. She wants to be a good mom. She’s recognizing all the benefits of being a good mom.

One thing that I don’t talk about a whole lot, with kids especially, is that Roz’s altruism isn’t necessarily coming from a true place of love and generosity. She’s kind and being good to these animals because she predicts that at some point they might return the favor.

Roz does good time and again. She takes care. She’s generous. She’s thoughtful. She’s kind. And at a certain point, I came to this thing where I was like, I don’t really care what her motivations are, even if her motivations are purely selfish. God, I wish every selfish person were like Roz because, man, the world would be a better place. So I kind of came around to this point of being like, well, even if her kindness is strategic, who cares? Because she sticks with it, and that says something, too. The fact that she chooses to be kind again and again and again actually tells us in a weird, meta way that she’s really a good character after all.

But it’s a little bit more complicated than I think most people give her credit for.

In the world of these books, Roz and other robots like her were built to work for humans, to fill roles in industry and in homes—to be useful. At least in the context of this wild island, the way Roz becomes useful is by caring for others.

In our world, I am immersed in these conversations about caregiving and how undervalued it is. But here is this robot made with productivity in mind and the thing she does to fulfill her design is to care for her others in her circle. As the story progresses, that circle grows with each book.

It’s beautiful and it feels, again, this sort of back door into a bigger message about taking care of one another that is so poignant, precisely because she is a robot.

Brown: One of my goals for the first book was to show this sort of mechanical figure, this robot becoming almost more wild and natural than a person ever could, which seems so unexpected. It sort of makes sense how she, because of her abilities and her observation skills and her mimicry skills and all this stuff, how she’s able to actually connect with that natural world better than a person could.

In the second book, it’s sort of like, well, what happens when that wild robot then has to survive in civilization? How does that robot then interact with people and other robots, and what is her relationship like with, instead of a young goose, a young human or two of them?

I always like to tell kids that one of the big takeaways from this book is that Roz realizes that kindness is a survival skill. She uses kindness to survive in the wilderness, and then she uses kindness to survive in civilization. And even in the third book, she’s using kindness to win over different characters. And I love that idea.

It’s really at the core of who I am and what kind of stories I gravitate towards. I want to make stories that remind people of the value of being good to each other. It seems so hokey, which is why it’s great that I found these characters where I can kind of disguise those hokey themes in an exciting package.

I think if you were writing a similar story among humans, that value would be masked in some way or harder to draw out because of what we expect a mother to be just naturally. So the hokeyness—you’re almost able to really highlight it on multiple levels because she’s a robot, but also because she’s a robot mother.

Brown: Yeah. Well, I feel like I got away with something. I stumbled into this.

I had my own motivations to start the first book, and then I started discovering these little opportunities for tucking away these themes and these ideas that seem kind of cheesy and on the nose. But then, it doesn’t feel on the nose. It feels right for the story. It’s like this little weird sci-fi fable, and it’s okay to talk about these issues.

I’m a pretty tough critic. I watch a lot of movies. I read a lot of books. I’m very quick to criticize things, and I kept looking at my own work and thinking, ‘I feel like I’m getting away with this. I feel like it’s okay to have these themes be so obvious.’ It made me a little nervous at first, but I just kept going for it, and it kind of kept working as far as I could tell.

Near the end of book two, Roz meets her maker, a woman named Dr. Molovo. Each has many questions for the other. It’s my favorite parts of this series. At one point, Roz says to Dr. Molovo, “You created me. In a way, I am your child and you are my mother.” Dr. Molovo tells her no. And you write, “‘I am not your mother,’ repeated Roz. ‘Those were my very first words to Brightbill. And I was wrong.’”

What is the distinction you were drawing there—mother and not?

Brown: Roz has kind of come to think of motherhood in a certain way, and Dr. Molovo, who’s never actually had a family herself, wants to be clear that she doesn’t feel necessarily like— she’s a creator, but that doesn’t necessarily make her a mother.

The climactic moment for me actually in the second book isn’t Roz being chased through the city by other robots, it’s Roz meeting her creator and having that conversation. I just love the idea that these two characters are sitting there having this thoughtful conversation about parenthood, agreeing and disagreeing and all this stuff. And so that was one of the big goals, just to have that moment happen.

It’s brilliant. And it was another place that the story seemed, to me, to fit the science in an interesting way. The parental brain is shaped by our experiences, really, not necessarily by biological relatedness. The thing that makes you into a parent at a neurobiological level is the attention and time that you’ve given to a child, the practice of reading their needs, struggling to understand them, and meeting them—making mistakes and doing better the next time.

Dr. Molovo made Roz. She put the pieces together—it’s kind of her DNA, in a way. But Roz has cared for others, has given that attention and that time, in particular to Brightbill.

Brown: Roz is at this point—I think all the readers would agree, Roz is a mom. And it’s just kind of another one of those weird little moral dilemmas in the story.

So much of my job is to make this story as simple as possible. But some of the stuff I wanted to leave complicated. Some of the stuff I wanted to leave a little messy. And I love this idea that this tough, scrappy robot designer lady is almost—I mean, they both have found a sort of motherhood in their own way, but they still don’t even quite know how to talk about it.

Right. I mean, Dr. Molovo says, oh, I’m not your mother, but then she goes to these great lengths to save Roz and to give her this other future. It’s beautiful.

One thing I really love in book three is that Roz has learned how to care for others and now she goes on this hero’s journey, out into the world to try to save the people that she cares about. It’s not all that common for a character who is a mother to be at the center of the hero’s journey. And I loved that. Did you think about that framework, or that archetype, in writing this book?

Brown: Well, yes. I did. The driving force behind her, the whole time, is her feeling of love for her son. Then she finds out she’s going to be a grandmother, and she feels even stronger. There’s a scene, right before she leaves the island, when Brightbill says, “It feels weird bringing goslings into such a scary world.” And Roz says something like, “Well, when I feel scared, I think of you, and that makes me feel stronger. And now I know I’ve got grand-goslings coming, and it makes me feel even stronger still.”

She left [to try to save the island] because she was a mother and because she was going to be a grandmother. I don't know if I had actually put those words together like that, but a mother hero’s journey is a great way to put it.

Then, there’s this scene where she meets an octopus who talks about her own relationship with her offspring, and how she’ll never get to meet them, but she already loves them and she wants to protect them. [Later] she overhears a conversation where another mother is having her own issues with her children and—I just liked showing a mom going to extreme lengths to save her loved ones, and then also meeting other moms along the way and seeing how they’re doing their thing.

In large part, these stories are really an exploration of a different kind of motherhood. I have no doubt that has a lot to do with my own upbringing with my mom. She struggled with all sorts of mental health issues. Life was not easy, and she was not a great mom. She had clinical depression and dissociative disorder, and it was bad. But she got help, and eventually it really started working. And so she had a good 10 or 15 years at the end before she passed away.

There’s a line in the first book when Roz is getting advice from the other geese about mothering, and one of them says something to the effect of, “All Brightbill really needs is to know you're trying your best.” That really kind of encapsulates, for me, a lot of parenthood.

I mean, it’s not enough. You have to actually succeed at times. But I remember one thing that got me through my upbringing was looking at my mom, who was really not a very good mom, and realizing she was trying her best. And I think that realization allowed me to, I don't know, accept her, accept the situation, still find a way to survive and thrive and all that stuff. And so I love that line in the first book. And I think we’re watching Roz try her best every step of the way.

Did your mom get to read The Wild Robot?

Brown: I know she read the first one and she loved it. She was proud of me.

I have to ask you one more question, about artificial intelligence. So much of the conversation round AI right now feels so scary, and I wonder—maybe this is a stretch—Roz makes me think about what could happen if we created AI that reflected the best of us and the way that we are programmed to care for one another. Is that too pollyanna?

Brown: I’m with you. One of the reasons that I was excited about these books in the beginning was because so much sci-fi is dystopian. So many robot stories are dystopian. I like the idea of writing a story where the robot doesn’t rise up—I mean, it’s not that simple. I would say, actually, Roz’s and the robots’ existence is slightly dystopian, but it’s more of a utopia for most of the humans in that world.

But anyway, I’ve done plenty of reading and research on AI and robotics. I still wouldn’t call myself an expert, but I certainly hope that there are some guardrails that people or companies are putting in place to focus our energy in that direction, to have our robots be good and not bad, to maybe model them after our best traits and not our worst traits. It’s going to be tough, because at the end of the day, there are people designing these things.

And they’re not all Dr. Molovo.

Brown: No, they don’t all have good intentions.

I don’t have any great answers, but I like the idea that Roz is an example of how this could turn out better than we expect. We’ll see.

A few months after this conversation, Brown and I met at a bakery halfway between our homes to prepare for our in-person event. He said something there, building on this last point, that I’m going to be thinking about for a long time.

Stories create the future. If every robot story is dystopian, he told me, then that’s the future we will create. This story is about empathy. It shows readers, through this sci-fi adventure, what it means to care for one another. The kids reading these stories now will be the real-life Dr. Molovos of the future, the creators of the robots and AI systems who will be part of our world. Giving them a vision for the future that prioritizes caring for one another is so important.

And then there’s this: Right now, AI systems are learning how to behave in part from the stories we tell. What would it mean for AI programs to digest Roz’s story and, in doing so encounter one of their own, a robot who has learned, in her own best interest, to be curious, compassionate and, ultimately, loving?

One more for the bookshelf: While you’re picking up a boxed set of the Wild Robot books, check out X. Fang’s debut picture book, Dim Sum Palace. It’s a sweet reimagining of Maurice Sendak’s In the Night Kitchen, another family favorite.

Fang and Brown are married and expecting their first child early next year.

Wonderful interview, Chelsea! I love Peter Brown’s work and looking forward to reading the Wild Robot Book Series with my daughter. Fang’s debut book looks amazing!