I was cleaning out some old files recently when I came across a message in a bottle sent from across a vast sea: the discharge papers from the birth of my first child.

Among the standard issue “taking care of baby” and “taking care of yourself” pamphlets, there was a yellow worksheet for tracking newborn feedings and diapers, with detailed margin notes in a mix of my husband’s handwriting and my own. There was the discharge record itself, where hospital staff had ticked the “heritage unknown” box, despite the fact that my husband, who is Korean, and I were present the whole time, and they could have simply asked1.

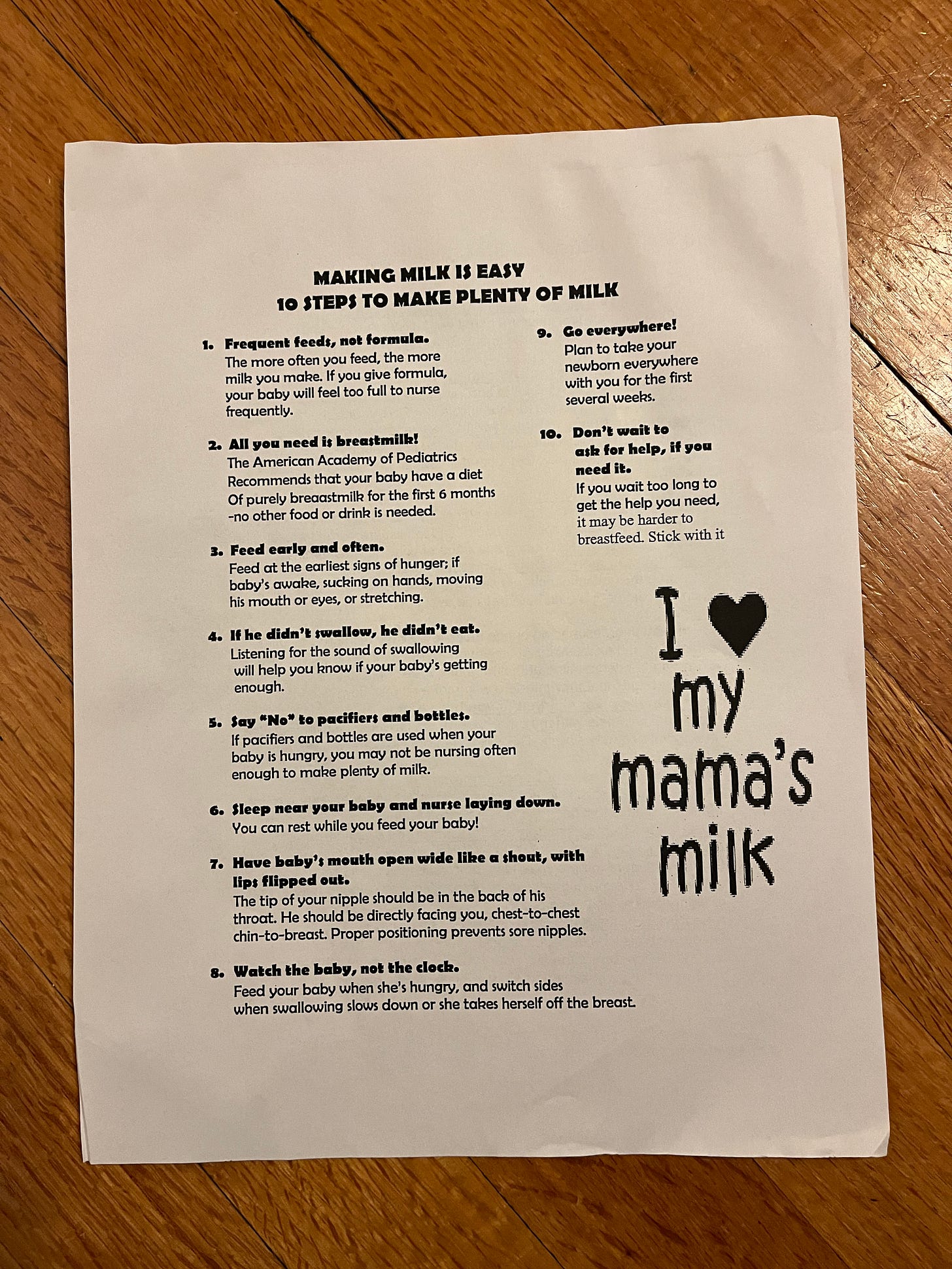

And then, there was this:

I did not remember this handout, specifically, but its message was very familiar. So was the weight on my chest.

Our son had been born small, after a long induction triggered by a spike in my blood pressure. In the hours after delivery, the nurses coached us on teaching him to suck. The hospital lactation team helped me to hand-express colostrum and attempt nursing every three hours. They assured us we were doing everything right—just keep going—but my milk was slow to come in, and our son was losing precious weight. The on-duty pediatrician suggested we supplement with formula.

But, you see, this was 2015, when breastfeeding rates in the United States reached a high point, the result of public health campaigns that urged hospitals to emphasize the benefits of breastfeeding at the individual level.

“Breast is best” was the dominant mantra of the day. The World Health Organization then, as now, called exclusive breastfeeding the “cornerstone” of child health, linked to higher intelligence and better long-term outcomes. Online pregnancy and new motherhood forums emphasized breastfeeding as the biological norm—the gateway to bonding—and promoted the idea that even a brief use of formula could alter a baby’s gut microbiome, with long-lasting effects.

The “fed is best” campaign wouldn’t launch for another year, and it would be several more before we’d see a wider cultural conversation, spurred in part by

’s Cribsheet, about how the individual benefits of breastfeeding—and the inferred risks of formula—were often inflated, the evidence, especially for long-term health impacts, generally weak and certainly not causal.It should have been a simple choice, to add formula to our feeding plan as I worked to build up my milk supply. Instead, it was agonizing. Eventually, the doctor stood at the foot of the hospital bed—loomed, really—and told us we couldn’t take our baby home unless we agreed. It wasn’t our choice anymore.

In the blue light of early morning on discharge day, a nurse sat next to me with a furrowed brow. She spoke low and slow. This is how it can start, I remember her saying. What are you talking about? Postpartum depression, she said.

But, I was fine. I was focused. I was trying to make the rightest decisions I could.

The nurse did not recommend that I check in with my OB-GYN about my mental health in the days to come. She didn’t give me resources for followup. Instead, at some point in the hours that followed, someone handed me this flier with the cheery clip art promising 10 easy steps to “make plenty of milk.”

We went home with the supplies we needed to tape a tiny tube to my nipple to add formula to our nursing sessions in those early days. And, then, I kept breastfeeding.

I fed my son “early and often,” sometimes glued to an armchair for hours of cluster-feeding. I monitored his swallowing. I attended regular breastfeeding support groups at the hospital, where I rejoiced at weigh-ins that showed he was growing—we were doing it—but also wondered at how calm the other mothers seemed. Why weren’t they talking about how hard this was?

When I returned to work at three months postpartum, I pumped three times a day and once between night feedings to make enough, just barely, to fill his bottles the next day. I never, ever had a freezer stash, so I worried constantly about milk logistics, and that stress took a toll on my physical health.

Around five months, when it was clear my supply wasn’t enough, we started filling his bottles with a mix of breastmilk and formula, and I would wish we’d done it earlier. If only I could have known that one day our son would be a healthy, rail-thin 9-year-old who could eat his weight in bean tacos and who would outsmart me on a regular basis.

“[N]obody can look around a first or fifth grade classroom and tell which kids were breastfed,”

wrote recently on Burnt Toast. “As long as you have access to clean drinking water, breastfeeding is just far more optional than we want new moms to believe.”When I came across this flier, I felt full of compassion for the new mother who carried it home and full of disgust for whoever wrote it.

Could it have been outdated even in 2015, some remnant of a prior time that hospital staff simply hadn’t gotten around to refreshing? The pixelated script on the front is definitely post-1995 or so. That very deliberate “mama” suggests mid-2000s or later.

But, actually, who cares? The fact is, someone printed this for distribution in the year of our Lord 2015. And someone carried it to the hospital room where I was slowly getting myself dressed into street clothes, after spending days in mesh underwear and a robe.

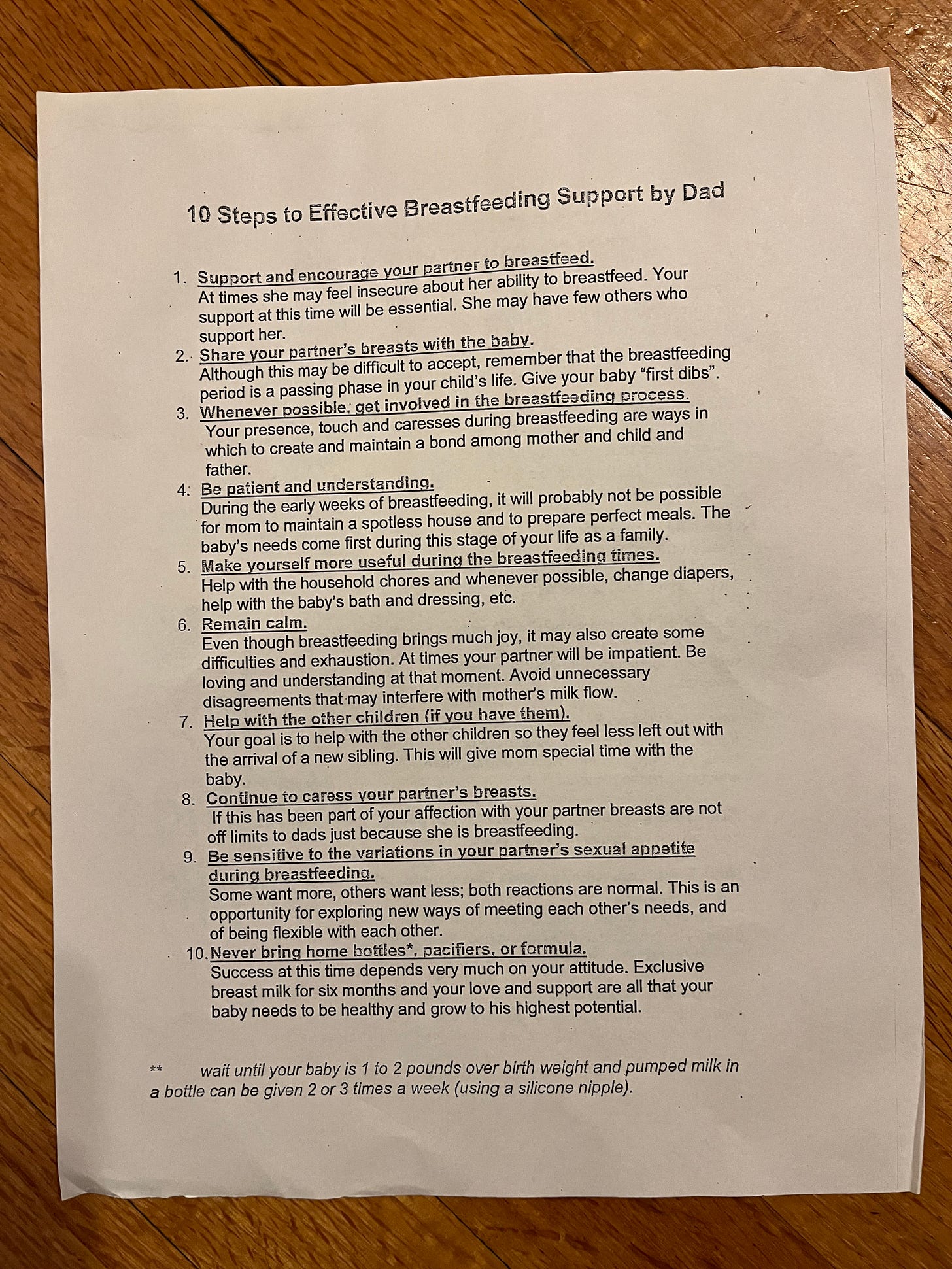

At least one of those someones should have known it was bullshit. If not for what the front of the page said, then for what was on the back:

When I shared these images on Instagram recently, a friend messaged asking whether this was satire from the Reductress. I wish I could say it was.

A few weeks ago, my sister gave me a small pile of papers she had pulled from one of our grandmother’s many plastic totes full of treasures. Nana saved everything. It was one of her defining traits.

Among them were type-written pages from her obstetrician, likely from the late 1940s, with strict instructions for pregnancy: no to high-balls, yes to wine or beer; no to crowded stores or long train travel, yes to light smoking; no to “sea-bathing” after six months, yes to hour-long afternoon naps “with clothes loosened.”

Then, there was a pamphlet printed by baby product company Mennen in 1954 with the frank title, “The 14 DAYS that can seem like a lifetime!” (The exclamation mark trying, and failing, to mask the dissonance between the message and the peachy illustrations.)

The pamphlet has all the markers of the era, including the White, Gerber Baby-like newborn, absolute deference to the male OB-GYN, and instructions to “give yourself and your husband a glimpse of the old femininity” as soon as possible. (No worse than “first dibs,” above.) But there’s also reassurances that the first weeks are hard, that feeding can be an anxious process, that outside support from a baby nurse or family members is absolutely necessary, and that bottles exist and need to be kept clean.

I do not idealize the time when my grandmother was raising children, at all. Clearly, the experts of Nana’s day got a lot wrong. But there’s so much we still haven’t gotten right today and some things we’ve certainly made worse.

We still have no federal paid parental leave program, no accessible community-based postpartum care, no reliable formula supply, no affordable child care—all things that offer the financial stability and support necessary for families to have real choice in how to care for their babies and to continue breastfeeding as long as they’d like. All things that other high-income countries have mostly figured out.

We still lack adequate research on the effects of breastfeeding and what we do have continues to focus on the correlational links between health benefits and breastfeeding, without adequately considering how feeding choices shape and reflect maternal mental health. Stress physiologist Molly Dickens recently dug into this topic on

.And, despite some recalibration in public messaging, “breast is best” remains dominant. Health communications researchers Susanna Foxworthy Scott and Jennifer J. Bute have called it a “master narrative,” or one that reflects a collective understanding across a culture. This one, they wrote in a study published last month, is loaded with “inherent morality” and amplified by social media.

The researchers interviewed mothers of infants who had ever used formula about their own feeding choices and how those choices shaped their maternal identities.

“Instead of understanding breastfeeding as a complex biological, psychological, and social process that is value-neutral, women interpreted that breastfeeding is a choice that defines one as a good mother who can bond with their baby,” they wrote (emphasis, mine).

I’m sure the motivation of whomever wrote that flier was to provide encouragement, to show new mothers a path to success in breastfeeding—a natural, normal path. An easy one.

Except pregnancy is messy and complicated, the paths into new parenthood diverging again and again. Like so many of the narratives around this developmental stage, the one about breastfeeding has been oversimplified—whitewashed—to such a degree that one might even think it’s deliberate. Real support for new parents requires honest accounting.

Yes, pregnancy, childbirth and lactation are normal and natural and often beautiful. And:

Pregnancy is risky.

Childbirth can be traumatic and unpredictable.

New parents are vulnerable and need a ton of support.

Making milk is hard.

Of course, they knew: The nurses debated over whether our son was jaundiced. One, who had been a favorite up until that point—brash and tough, someone you feel has your back—recounted the conversation to us. Of course he’s a little yellow, she had told her colleagues. He’s Asian!

SHARE YOUR PARTNER'S BREASTS WITH THE BABY. I am never going to be over this.

I love how the picture on the pamphlet makes it look like you just go and pick up your baby curbside 😆 giving birth has never been so easy